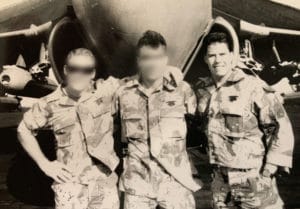

All photos courtesy Dan Tabor

Dan Tabor in his pre-SEAL days with his mother Dorothy Cornelius and his infant son. In the following two years he would successfully complete BUD/S and continue to serve another 19 years with the Navy SEAL Teams.

The only Oneida Nation citizen, to date, to have earned the right to wear the coveted “Trident” insignia of the United States Navy SEALs turned 60 years old September 22.

The only Oneida Nation citizen, to date, to have earned the right to wear the coveted “Trident” insignia of the United States Navy SEALs turned 60 years old September 22.

SOC (Ret) SEAL Dan Tabor, a 22-year veteran of the Navy, nineteen of which were spent as an operator and instructor with the SEAL Teams, reflected on his military career in a recent interview with the Kalihwisaks.

The son of Air Force Veterans, Dorothy Cornelius and Donald Tabor, the future frogman grew up on the southeast side of Chicago where he attended Lutheran church and became an accomplished high school athlete. By the time he graduated from George Washington High School, Tabor had lettered five times in wrestling and swimming.

“That was a really good base for going into the SEALs because I could swim and I was physical,” Tabor says. “I graduated at 17 and was a bit small, but by the time I turned 19 I hit a growth spurt and shot up to 210 pounds right before I joined the Navy.”

Upon enlisting in the Navy in 1984, Tabor received some good-natured teasing about not joining the Air Force like his parents. He would joke that he was simply the ‘black sheep.’

“The guys I knew that were in the Navy loved it so much and just seemed so cool that I decided to go that route. I’ve never looked back.”

After finishing boot camp Tabor began extensive training to become an air crewman on CH-46 helicopters. The part of training he was most looking forward to was the Search and Rescue (SAR) swimming.

In a bizarre twist of military abnormality, Tabor wasn’t allowed to become a SAR swimmer because of an apparent depth-perception issue.

“I was the best swimmer in my SAR class, but right before graduation I was pulled because I couldn’t tell which ring device was closest to me right away. So, I was allowed to become an air crewman but I couldn’t deploy in the water and pick people up. Then, when I put in for SEAL training, I passed all my eye tests perfectly. So, go figure, I couldn’t become a Navy rescue swimmer but I ended up becoming a Navy SEAL,” Tabor says with a laugh.

“I first served as an air crew member flying onboard CH-46 Sea Knights,” Tabor says. “I had made two Western Pacific cruises and towards the end of the second deployment we picked up some SEALs. That encounter really put the bug in me. These guys wanted to go skydiving in Subic Bay (Philippines), and they told me if we could set up a jump for them they’d help explain how I could get into the SEAL pipeline. Well, we set it up with some of the younger pilots, and these guys came walking off the bus for their jump wearing UDT (Underwater Demolition Team) shorts, Teva sandals, and their parachutes. No headgear, no shirts, and I thought ‘Man, these guys are so cool, I’m hooked.’”

The unit name SEAL stands for Sea, Air, and Land, the environments that these highly skilled warriors operate in. The modern Navy SEAL Teams owe their lineage to the famed UDTs of WWII who scouted and cleared beachheads for amphibious invasions like those executed on D-Day.

Tabor arrived at Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, just outside of San Diego, California, in 1988 in excellent physical condition for SEAL training. Known as BUD/S (Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL), the initial SEAL training course is a six-month selection process widely considered to be the toughest military training on the planet.

Divided into three 8-week phases, BUD/S pushes every candidate to their physical and mental breaking point which is why students must be fully prepared, mentally and physically, upon arrival.

“I was the best swimmer in my SAR class and one of the top runners,” Tabor says. “When I got to BUD/S, no joke, I was a nobody. There were so many incredible athletes in my class that I never even saw the guy that finished first in the four-mile timed runs. These guys were nothing short of phenomenal.”

The then-Petty Officer Tabor survived his six-months of training at BUD/S, including the notorious Hell Week, during which trainees receive no more than four hours of accumulated sleep across a six-day period, and Pool Comp (essentially Hell Week underwater) while on his way to graduation. Statistically, nearly 80 percent of all SEAL hopefuls will wash out of training and never realize their dream.

Tabor’s first duty assignment to an operational team was with Virginia Beach’s SEAL Team Two, where he was dubbed “Dano” by his teammates.

“That was the best thing in the world because I absolutely loved Two,” says Tabor. “Two was the powerhouse, full of studs team. I was a pretty big guy, but when I got to Two I kept my mouth shut around those guys. There were just a ton of tough, tough, guys there.”

There was also an incredible history in SEAL Team Two, most of which will never be available for public examination.

“I was so fortunate because legendary Master Chief Rudy Boesch was still walking the halls, and Medal of Honor recipient Mike Thornton would cruise through once in a while. That team was just full of so many heroes that you will never hear about.”

Life in The Teams is non-stop hustle and extremely dangerous.

“My team was conducting ship take-downs during Desert Shield/Storm and our helo went into the water with 20 guys onboard,” Tabor says. “The crewmen and my whole platoon of SEALs were on an H-3 Sikorsky when we hit the water at over 80 knots. Fortunately we had an experienced pilot who was able to keep it nose up, but then the tail rotor hit and we started spinning. But he kept the bird flat and we didn’t flip. We ended up in the water for over two hours and it did eventually flip and sink.

“We had seen so many hammerhead sharks in the water a few days earlier on a previous op, but there must have been enough JP-5 (jet fuel) from the crashed helo that they weren’t a threat,” Tabor says with a laugh. “A CH-53 arrives to pick us up and the helicopter crewman kicks the life raft out to us. But he forgot to hook it to the airframe before sending it out. This activates the cartridge that inflates the raft, so he sent it out and it hit the water and sank. Another Sikorsky, exactly like the one we had just crashed in, finally shows up and starts hoisting us up. I remember flying back to our ship and seeing another Sikorsky on its way out to pick up the rest of our guys because we didn’t want to hit any weight issues on the rescue birds.”

During Tabor’s Desert Shield/Storm deployment with SEAL Team Two, life brought a major blessing, albeit one he was unable to attend.

“I was laying in my rack on the USS Kennedy and I remember my Lieutenant saying, ‘Hey Dan, your wife just had a baby girl.’ He handed me a piece of paper from the Radio Department and that’s how I found out my daughter was born. I didn’t get to see her until she was over three months old. No pictures- nothing. These days if a team is experiencing a high operational tempo, they’ll send the father home for a short time because we can get back and forth fairly quickly now.”

Another potential downside to becoming a SEAL is there are no typical nine-to-five, Monday through Friday assignments. This doesn’t make for a stable family life and divorce rates among these all-male commando units are high.

“I ended up getting divorced from my first wife because we were just gone so much. I was in the Navy before I got married, but it’s so tough on families and you miss a lot of birthdays.”

Following three hitches with SEAL Team Two, Tabor headed back to the West Coast for another two with SEAL Team Three before being called upon to become a BUD/S instructor. However, right before he could begin training students, life as we all knew it changed.

“I was on leave getting ready to transfer to BUD/S and then 9/11 happened,” Tabor recalls. “When that went down I had to ride my bike into the compound because there was no getting onto or off that base in a vehicle. Our guys were on top of the buildings locked and loaded and ready to rock and roll. I called the detailer right away and told him I wanted to stay with Team Three because I knew where they were headed. I was told ‘no’ and kept my BUD/S orders, but I did get to deploy over there in 2004.”

That joint SEAL Team deployment to the Middle East would be his last. Every SEAL knows when you play the game long enough, injuries are inevitable.

“I jumped out of a Humvee and twisted my knee,” Tabor says. “I was 43 at the time, and when we got back to Coronado I ripped up my meniscus pretty badly. I then spent a good 15 years after that grinding away on that knee and it finally got to the point that I had to get it replaced a few years ago.”

By the time he called it a career in the Navy, the now-Chief Tabor had deployed eight times, participated in more missions with The Teams than he can count, and put numerous would-be frogmen through BUD/S. Finding it impossible to stay away from the camaraderie of his close-knit brotherhood, Tabor now spends his time working as a contractor putting other SEALs through land warfare training.

“The funny thing is some of these SEALs are guys I put through BUD/S, and now they’re my boss,” Tabor laughs.

Although he didn’t spend a significant amount of time on the Oneida Reservation during his formative years, Tabor is more than familiar with his family, his Native heritage, and the Oneida warriors that came before him.

Although he didn’t spend a significant amount of time on the Oneida Reservation during his formative years, Tabor is more than familiar with his family, his Native heritage, and the Oneida warriors that came before him.

“My mom Dorothy Cornelius was born and raised in Oneida in 1933 and was the youngest of ten kids,” recalls Tabor. “Her siblings were Hayward, Leo, Billy, Dempsey, Louie, Ruth, Rebecca, Margie, and Mary. My uncle Kenny House was an iron worker who helped build the Sears Tower, and that’s how we ended up in Chicago because some of the sisters’ husbands were also union iron workers.

“My uncle Dempsey Cornelius, who just turned 100 years old, is a Bronze Star recipient from WWII. I just love him so much and I’m so glad I have his blood in me, warrior to warrior.

“I got choked up when Ernie Stevens Jr. asked if I’d be able to make it up to the Oneida Pow Wow in 2005 for my eagle feather presentation. I had given a tour of the Naval Special Warfare training facility (BUD/S) to him and several elder Oneida warriors, so when I was asked to come to the Pow Wow and help lead the Grand Entry, I was honored,” Tabor says.

“I walked out with the veterans for the Grand Entry and it was fantastic. Uncle Dempsey was there along with almost all of my Cornelius, Hill, and Skenandore cousins. In addition to my eagle feather presentation, Oneida warrior and artist Kenny Metoxen presented me with an amazing tomahawk he handmade that I still show off to my buddies to this very day. That thing is so authentic it would crack a Kevlar helmet.”

Fully aware of his ethnicity, Tabor always made it a point to keep an eye out for any Native Americans entering the SEAL pipeline.

“There haven’t been a lot of Native Americans that went through SEAL training, so when I became aware of anybody I would always make the effort to get to know them.”

The United States Navy offers recruits a chance at the adventure of a lifetime with vast job opportunities. For young people considering a career in The Teams, the best advice the former BUD/S instructor has is to simply go for it.

“Take the chance because who knows what you are capable of. Don’t be afraid to try and fail because you’ll almost always have another chance when you’re young. Where there’s no risk, there’s no reward. Don’t be afraid to try because in today’s climate we need more SEALs than ever.”

BUD/S is tough for a reason, and it’s often the little things that speak volumes to the instructors.

BUD/S is tough for a reason, and it’s often the little things that speak volumes to the instructors.

“Believe it or not, the goal of BUD/S is to try and get you through, but it is not going to be easy. We mess with the guys because it’s necessary. We’re going to put your entire class into that cold water until someone quits (known as ‘surf conditioning’), because if that makes you quit….we need to know that you’re not going to bail out on us when it gets real and the bullets start flying.

“If you make it to The Teams you’re almost like a Ferrari,” Tabor explains. “The Navy has just spent a lot of money training you and turning you into a warrior, so once you get to your team they’re going to expect you to deploy. There’s no asking for days off. With BUD/S, another six months of SQT (SEAL Qualification Training), all your pre-deployment workups, they are preparing you for war. I will always tell young people that being in the military means you’ll be asked to step up and fight for your country, and that’s especially true in The Teams. When you’re a SEAL and they tell you that you’re deploying, you’re going- and you’re going to be expected to fight. Sometimes that’s a very hard pill to swallow for some young guys.”

These days the retired frogman continues to work in the Naval Special Warfare community, and he wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Man, I absolutely loved being a Team guy. I got to work with some of the most amazing people in the world and I wouldn’t change a thing. Being able to still work in the community when I was retiring was something I hadn’t quite expected, but they came and asked for me specifically and there was no way I was going to say ‘no.’”

Having a more stable home life in retirement without all the demanding deployments has also gone over well with his children.

“Obviously he was deployed a lot when I was growing up,” Tabor’s now adult son says. “But for most of my elementary and middle school years he was a BUD/S instructor, and my favorite part of that was during the summer I got to go to work with him and watch him hammer on the students. That was so cool for young me to see, because then I knew I wasn’t the only one getting yelled at for getting in trouble. Turns out there were a whole lot of other guys as well.

“Obviously he was deployed a lot when I was growing up,” Tabor’s now adult son says. “But for most of my elementary and middle school years he was a BUD/S instructor, and my favorite part of that was during the summer I got to go to work with him and watch him hammer on the students. That was so cool for young me to see, because then I knew I wasn’t the only one getting yelled at for getting in trouble. Turns out there were a whole lot of other guys as well.

“He was a great dad who never brought his work home,” his son continues. “Obviously if I got in trouble, I deserved what I got, but it was cool as a young man to see what my dad did firsthand in a teaching capacity. Even though he was harsh, he took it upon himself to lead the way and set the example for the students. His job was to be hard on the them because they have to be tough given the nature of what SEALs do. But he would also take students aside and give them guidance because the water can only be so cold, and the training can only last so long.

“As I got older he deployed again and I was very fortunate to have my dad come home safe because a lot of other kids didn’t get that chance. I am very grateful for that and as I got older it really hit home thinking about other people who didn’t have that opportunity. I love my dad and I would do anything for him. It’s really cool to have him here and now we get to hang out and spend the rest of our lives together.”

His ethnicity isn’t lost on the younger Tabor, either.

“Being Native American is a real source of pride and it means a lot. We’re not 100 percent but it is really special. My grandmother Dorothy was a great lady and I really miss her. She raised a great son and I’m so fortunate for that because from her through him I feel like I was raised very well also.”

And the daughter who was born while her dad was busy chasing bad guys in the Persian Gulf? She’s also all grown up now and is beyond proud of everything her warrior father has accomplished.

“Growing up I didn’t really understand what my dad did for a living,” she says. “All I knew was that he had an important job and he had to be away which was hard, and my brother and I would receive post cards from his travels. He was trying to do right by us, because he wanted a stable job and he was very proud of what he was a part of.

“I’m also proud of the sacrifices he made because sometimes certain people have to put their careers first for the greater good. But I had a happy childhood and I wish people would be more appreciative of the men and women who have jobs like this. They don’t always get to spend time with their kids because they’re here to protect everybody. The pivotal point for me was knowing the bad men in this world who would still be here if it weren’t for the type of men like my dad.

“I know he’s proud of his career and it’s just crazy knowing my dad is this total (tough guy),” says his daughter. “I didn’t envy anybody who crossed him when he was in his prime. You see all these Marvel superhero movies; well my dad was the real deal. He’s one of the silent heroes you never hear about and I want to thank him. I know it wasn’t easy and I know he had to make some tough choices for himself, but in the end it was all for the greater good. I love you, dad.”

“I know who Valder John was,” says Tabor. “Jim Overman who flew 300 consecutive missions in an AC-130 during Vietnam, uncle Dempsey, Loretta Metoxen, and all the other Oneida Nation warriors. I am truly honored and humbled to be among them.”

Dan Tabor has remarried and expanded his immediate family. He resides on the West Coast.